5.1 INTRODUCTION

5.1.1 Para 6.6(5) of the Study Brief states that the consultants shall "identify...a pattern of draft LCT and LCA at a scale of 1:10,000 which will be verified in the field survey".

5.1.2 This Chapter is concerned with this particular item of Task 5 only and will address:

The objectives of preparation of a preliminary pattern of LCT/LCAs (hereafter called the 'Preliminary Landscape Character Map';

Review of methods alternative methods for producing the 'Preliminary Landscape Character Map';

Proposed methodology for producing the 'Preliminary Landscape Character Map';

Results of Test Exercise; and

Proposed Future Work.

5.2 THE OBJECTIVES OF THE PRELIMINARY LANDSCAPE CHARACTER MAP

5.2.1 In order to achieve a more objective, rational and consistent approach to landscape classification, it is now common practice in the field of landscape mapping and landscape assessment, to use computer based modelling techniques to produce a Preliminary Landscape Character Map (PLCM). This preliminary map can then be checked, verified or amended in the field by landscape architects. Verification and amendment in the field allows the more emotive and visual components of landscape to be added to what is otherwise a formal and rational classification. Such techniques are generally GIS-based.

5.2.2 The objective of this process is to employ the powerful potential of GIS for consistent and rational data handling to analyse the coincidence of various landscape features (presented to the computer in digital format) and so define a preliminary map showing Landscape Character Types/Areas.

5.2.3 It should be noted that it is not intended that the procedure be used to produce the finalised definitive map, but rather to identify the majority of Landscape Character Areas (LCAs) within the Territory. It is recognised that this will need to be followed up with comprehensive field work, the results of which will be fed into a revision of the map.

5.3

REVIEW OF AVAILABLE GIS-BASED TECHNIQUES

5.3.1 Before selecting a method to produce the Preliminary Landscape Character Map, a number of criteria were defined which it was felt that the appropriate technique must meet. These were:

Reasonable level of potential accuracy;

Potential appropriateness for small-scale and urban landscapes;

Availability and compatibility of technical data / software;

Ease of application and interpretation.

5.3.2 Four possible GIS based methods have been examined as follows:

TWIN SPAN;

Weights of Evidence method;

FRAGSTATs method; and

Data Treatment of existing GIS data and Rule-based Treatment based on existing GIS data.

5.3.3 TWINSPAN (Two-way Indicator Species Analysis) is a FORTRAN-based multivariate technique developed originally for identifying clusters of ecological indicator species and areas of similar species composition. It operates by identifying key correlations between given environmental variables. TWINSPAN has occasionally been used in UK for landscape mapping, particularly on large-scale strategic studies. The technique does have two potential draw-backs. Firstly, it is not a GIS-based technique and so requires interfacing with GIS. Secondly, studies which involve large numbers of small-scale LCTs and LCAs (see Oughtrington and Heatley Community Landscape Plan, University of Manchester, 1993) suggest that TWINSPAN may not be appropriate for capturing the complex and subtle changes which operate at very local landscape levels, such as those in the current Study. Finally, it is not known whether TWINSPAN has been used in urban classifications and so its practical applicability for this task is not clear.

5.3.4 Weights of Evidence is a technique originally developed for medical applications but recently adapted for use in the minerals and geological industries in order to identify geological deposits. Similar to the methods of multiple regression in statistics, the Weights of Evidence model for combining evidence involves the estimation of response variable (favourability for mineral deposits) and a set of predictor variables (exploration datasets in map form). It is felt that technical issues relating to its precise operating procedures and the fact that this technique had not before been applied to landscape, makes it less suitable than the proposed methodology for the current Study.

5.3.5 FRAGSTATs is a GIS-based routine developed primarily for use in landscape ecology which rather than identifying homogenous areas of landscape, is used for statistical analysis of areas that are already defined. Though the technique has certain applications in the field of landscape planning, it is not appropriate for the production of the Preliminary Landscape Character Map.

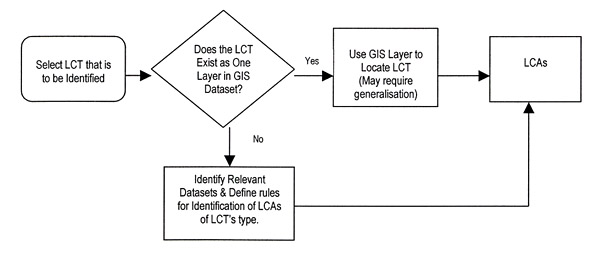

5.3.6 The final technique investigated for use was that of Data Treatment and Rule-based Treatment of existing digital data. The methodology assumes that Landscape Character Types (LCTs) will either be able to be derived from one of two possible sources:

Direct from a single dataset. This technique is known as Data Treatment. This technique is appropriate where a single environmental variable defines the character of an LCT and that variable is already available on a single data layer. The Data Treatment technique could be used to directly define Rocky Shorelines LCT, Gei Wei LCT and Mud Flats LCT, which are LCTs whose single dominant characteristic is already available as a digital dataset.

Indirectly, by calculating the likelihood of a given area belonging to a particular LCT, based on combinations of physical environmental features in that area. These can be calculated in various ways including image processing based techniques or GIS based classification techniques. The technique, termed Rule-based Treatment, is appropriate where the character of an LCT cannot be defined from a single existing dataset, but must be interpolated through the relationships of a number of existing datasets. Initially it was expected that image processing based Supervised Classification would be used to identify LCAs. However, the procedure produced results of insufficient detail. The procedure has been modified slightly and now utilises GIS-based rule-based procedures to delineate LCAs. Using this approach, for each LCT a series of rules have been developed (as shown in Appendix 4) that allow LCAs of that type to be derived. An example of an LCT where this technique could be used would be the 'High-rise Waterfront Housing' LCT. This LCT is likely to occur in areas 'near' to the coast where 'high' residential buildings occur. Digital data exists for each of the components making up this LCT and it is assumed that by using the computational technique of Rule-based Treatment, these types of LCT can, for the most part, be derived.

5.3.7 During initial trailing of the method, it was found that the best results were obtained by treating 'Developed' and 'Non-developed' landscapes differently. Non-developed LCA boundaries have been established using delineations between various environmental and topographic features. Boundaries for developed categories have been derived by assessing the predominant LCT for each of the polygons in PlanDíŽs street block boundary dataset.

5.3.8 The Data Treatment / Rule-based Treatment technique has the following positive attributes:

Relative simplicity of operation compared to other techniques;

The ability to 'train' the system to identify areas where a predetermined set of LCTs arise;

GIS based-technique and therefore readily compatible with both data inputs and final Study output;

Classification process can be carried out rapidly and the product re-generated rapidly.

5.3.9 The Study Team considers this technique to be of greatest potential value to the Study. The procedure is discussed in more detail below.

5.4

PROPOSED DATA TREATMENT/RULE-BASED METHODOLOGY

General Approach

5.4.1 As mentioned above, the methodology assumes that an LCT for an area can be derived either directly from existing digital data or by developing rules for the treatment of a number of datasets to produce the LCT of that area. This treatment is described in Table 5.1 below.

Table 5.1 General Treatment for Defining and Mapping LCT/LCAs

5.4.2 Taking into account the draft final list of LCTs presented in Table 1.1 and using the supporting datasets constructed to support the PLCM, it is necessary to determine the appropriate treatment for identifying each LCT: either Data Treatment direct from a single existing dataset, or Rule-based Treatment, by interpolating a number of relevant datasets. The appropriate treatment and a description of the procedures for identification of each LCT is presented in Appendix 4.

Explanation of Data Treatment Technique

5.4.3 Treatment for LCTs that can be derived directly from a single existing digital dataset is simple as it only requires extraction of appropriate features from the source GIS data file. An example of this would be the Mangrove LCT. This can be extracted from a GIS habitat dataset created under the SUDEV21 study as a series of polygons and these polygons will be turned directly into LCAs. Some aggregation of small units into larger ones is required as LCAs in general should be 5ha or greater.

Explanation of Rule-based Treatment Technique

5.4.4 The general assumption behind this treatment is, as stated above, that the LCT into which any given area falls is related to a number of physical environmental features of that area. The selection of appropriate boundary defining methods for these LCTs is related to whether the LCT is Non-developed or Developed.

5.4.5 In the case of Non-developed LCTs, boundaries can be derived by establishing rules based on environmental characteristics of an area. For example, the 'Lowland Valleys LCT' (Rl(a)) typically occur below about 100mPD where concave slope patterns occur while 'Coastal Plain' (Rl(p)) typically occurs within a kilometre of the coast below 40mPD. By manipulating the supporting topographic data and vegetation data, it is possible do derive LCAs for the majority of Non-developed LCTs.

5.4.6 In the case of Developed LCTs, boundaries typically follow man-made features such as street block boundaries. LCAs can then be defined by looking at the combinations of features occurring on each street block. For this technique to work, these features need to exist as mapped datasets. For example, to identify LCAs which fall into the 'High-rise Waterfront Housing' LCT, it is necessary to have mapped layers showing:

building locations and height;

where the coastline is and

the land use zoning of the area (to help define 'residential').

5.4.7 GIS can then be used to identify street blocks containing a majority of high buildings (say above 40m), in residentially zoned areas close to the coast.

5.4.8 It should be noted that in a small number of cases, key data for distinguishing certain LCT from others (e.g. 'Walled Village' LCT from the other 'Village' LCTs) does not currently exist in digital format. Unless a layer of digital data containing 'village walls' can be obtained, there is no way for the program to distinguish this LCT and a coarser classification must be accepted and then refined manually. In this case, a number of Interim LCTs have been used for the purpose of production of the PLCM map. For example, all the village LCAs are in fact found on the PLCM as the Interim LCT 'Village Landscape'. Refinement and more discrete definition will take place during Field Survey and the correct LCTs will be presented in the Draft Landscape Character Map.

5.4.9 Interim LCTs currently in use are:

Rl(p)A which covers all Coastal Plain LCTs;

Rl(a)A refers to grassed Lowland Valley and is expected to have captured all instances of Lowland Valley Farmland LCTs;

Rl(a)B which covers Lowland Valley Floor LCTs;

DX(r)A which covers the LCTs of Du(r)3 and Df(r)2 which cannot be automatically distinguished;

Dg(v)A which covers all non-coastal village LCTs.

5.4.10 While generally successful, limitations exist with the above-described techniques for automatic identification of LCAs. As mentioned, there is in some cases simply not enough available digital data available to separate all LCTs that may be encountered. The treatment in these cases is either to verify during field survey or manually identify using aerial photographs.

5.4.11 Data gaps and problems encountered when attempting to generate LCAs for the PLCM are described in general in the following section and on an LCT-by-LCT basis in Appendix 4.

5.5

THE PRELIMINARY LANDSCAPE CHARACTER MAP (PLCM)

Introduction

5.5.1 The Preliminary Landscape Character Map (1:50,000), Sheets 1-4 is attached to this report. It sets out the preliminary pattern of LCTs/LCAs.

Methodology for Creating the PLCM

5.5.2 The rules by which LCTs are defined and classified are set out in Appendix 4.

5.5.3 In the case of Urban, Urban Fringe and Rural Fringe LCTs, classification proceeds by reference principally to land use and relies mainly on mutually exclusive criteria which are relatively well-defined. For example, an Airport can only be classified an Airport and a Golf Course only a Golf Course. Other developed LCTs can be defined by a combination of mutually exclusive attributes such as height of buildings, type of land use and density of building footprints. Appendix 4 contains descriptions and treatments of the data used either on its own or in combination to define each Developed LCT.

5.5.4 However, in certain cases, notably in the case of Rural LCTs, mutually exclusive classification criteria are not always available and the process of defining LCTs requires a sieving and prioritisation process which observes a series of rules. These rules are set out below:

Step A - Define 'Development' LCTs (Urban, Urban Fringe and Rural Fringe LCTs) first - in case of conflict with any other LCTs below, Development LCTs take precedence;

Step B - Define Coastal Landscape Types - in case of conflict with any other LCTs below, Coastal LCTs take precedence (except in the case of Valley LCTs);

Step C - Define 'Lowland LCTs' (all land<40mPD. 40mPD is a practical elevation which seems to define plains and their associated vegetation in Hong Kong);

Step D - Define land >300mPD, which become Peaks and Ridges LCTs. (300mPD is the altitude at which in almost all landscapes, scrub vegetation gives way to grassland);

Step E - Split Peaks and Ridges into grass-covered and scrub-covered depending on predominant land-cover;

Step F - Define Valley LCTs (using 200m DEM). Valleys are defined by using a computer model to identify all convex and concave slopes. These are then interpreted by hand such that 'Valleys' are deemed to include all flat and concave slopes within the valley morphology. Convex slopes are deemed to be uplands or peaks.) Use boundary of C above to define valley boundary where there is any conflict. (This takes precedence over B above);

Step G - Split Valley LCTs into Lowland Valleys and Upland Valleys depending on elevation above or below 100mPD contour (100mPD is a practical altitude at which significant settlement is deemed to be very rare);

Step H - Split Upland valley into Wooded upland valley and Scrub-covered upland valley depending on predominant land cover;

Step I - All remaining areas are to be 'Undulating Uplands and Hillsides' LCTs;

Step H - Undulating Uplands and Hillsides LCTs should be split according to predominant land cover into 'Wooded.' 'Scrub-covered' or 'Grass covered'.x 4.

LCA Numbering System

5.5.5 Polygons representing LCA boundaries in the PLCM each have a unique identifier. Originally it was thought that this identifier should help to describe the properties of the LCA (i.e. its LCT and location). Assigning attribute-based identifiers such as this at this stage is premature, as many of the LCAs will have their LCTs changed during field survey.

5.5.6 One of the reasons importance may have been placed on an attribute-based unique identifier for each LCA was so that surveyors could more easily tie field survey results to an LCA. By using a GIS during field survey, each LCA is uniquely identified through its geographic location stored in the system.

5.5.7 Observations made in the field about an LCA can be linked through the system to each LCA directly based on their location.

Discussion

5.5.8 It is important to appreciate that the PLCM is only a draft first attempt at mapping the landscape of Hong Kong. What has become evident to the Study team during this process is that in a Study such as this the process of remote landscape mapping can only be carried out to a certain level of accuracy. The process of remotely mapping a concept as subtle and sophisticated as 'landscape' is an extremely difficult one. Even the most sophisticated GIS or computer software (including those reviewed above) still has difficulty identifying and delimiting, something as apparently simple as, for example a 'valley'.

5.5.9 The limitations of the accuracy of the PLCM are due to a number of factors:

Data Gaps or Imperfections;

Alternative Data Sources;

The Very Fine Detail of LCTs/LCAs;

The Emotional Component of 'Landscape' and

Boundaries Issues.

5.5.10 These issues and the ways in which they have affected the PLCM are discussed below.

Data Gaps or Imperfections

5.5.11 In certain cases, data necessary to define an LCT was simply not available in a comprehensive or systematic format to enable that LCT to be plotted on the PLCM. An example of this is the 'Walled Village' LCT (Dg(v)4). No comprehensive data set exists defining the extent of walled villages in Hong Kong and for this reason they are not identified on the PLCM.

Alternative Data Sources

5.5.12 In certain cases, two or more alternative sources of data were available for a given landscape feature and a choice had to be made as to which data set should be employed. For example, both the SUSDEV21 Habitat Map and the Broad Land Utilization Study contain datasets for woodland. These are however, quite different and based on different criteria. The choice of which data set to use was made generally on the basis of what would most usefully serve the objectives of the Study.

Small Scale of LCTs/LCAs

5.5.13 In the case of this Study, the process of preparing the PLCM has been especially demanding due to the fine (5ha) scale at which mapping has been carried out. This has resulted in a very fine level of classification with subtle distinctions between a number of LCTs.

5.5.14 In turn, the high number of LCTs and the often-subtle distinctions between them, has proved in some cases difficult for a computer or GIS system to handle. The result is that in certain cases, the computer is simply not able to identify the difference between 'Low-rise housing suburban estate' (Df(r)2) and 'Resort-type development' (Dg(r)2) which are based on differences in layout and style of architecture or landscape.

The Emotional Component of 'Landscape'

5.5.15 What has become evident during the preparation of the PLCM, is that certain cases, there are quasi-emotional qualities which it is impossible for a computer to handle. For example, the difference between 'Historic Mixed Urban Landscape' (Du(m)3) is often a case of the size, visibility and character of historic buildings, which are complex perceptual and emotional issues which a computer may not be accurately able to deal with. In such cases, nominal thresholds have often been used to define LCTs, on the understanding that these need to be verified on site.

Boundaries Issues'

5.5.16 The rule based classification system requires a set of boundaries are areas to be defined to which the rules can be applied. In urban areas, the street block system has been used for this purpose, as streets are normally the best fixed feature at which a change in character can be marked. The use of the street block network can however occasionally result in anomalies. For example, where there is a very large street block which contains two areas of distinctly differing character, only one set of rules will be applied to that block and therefore the whole block will show up as a single LCT. Discrepancies such as this will be corrected during field survey.

Methods for Correcting and Updating the PLCM

5.5.17 Given the limitations identified above, a number of ways of refining or improving the results of the PLCM are available.

5.5.18 Manual interpretation is one way of ensuring that obvious errors in the PLCM are corrected. This has been used in the case of 'Power Station' landscapes (Dg(w)1) where the location and extent of the LCT is obvious. In other cases, manual interpretation is far less obvious and would not lead to an acceptable level of accuracy.

5.5.19 Updating during site survey is the best way to update and correct known (and unforeseen) shortcomings in the PLCM. It is also the only way in which the 'emotional' and visual component of landscape can be adequately captured. Therefore, in most cases, this is the proposed method of updating and correcting the PLCM.